NASHVILLE (BP) — The only four Baptist pastors in Georgia at the dawn of the American Revolution were so impressed with the 15-year-old’s testimony and gift of exhortation, they licensed him to preach.

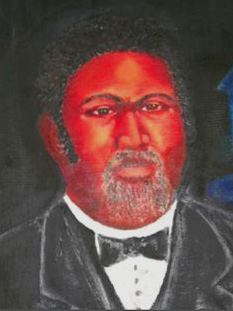

The older men were all wealthy white plantation owners, but the teenager was George Liele, an African enslaved by one of the pastors’ friends. Liele became the first ordained black Baptist preacher in the 13 colonies and proceeded to plant a church in Savannah, Ga., before sailing to Jamaica as the first Baptist missionary, black or otherwise, from the New World.

The older men were all wealthy white plantation owners, but the teenager was George Liele, an African enslaved by one of the pastors’ friends. Liele became the first ordained black Baptist preacher in the 13 colonies and proceeded to plant a church in Savannah, Ga., before sailing to Jamaica as the first Baptist missionary, black or otherwise, from the New World.

In the 2013 Mercer University Press book, “George Liele’s Life and Legacy,” the former slave is hailed as a brilliant peacemaker and unsung hero for the progress he made against odds and across racial and social boundaries.

Many Baptist historians have heard Liele’s name but few know his significance to the denomination, said Carlisle Driggers, executive director emeritus of the South Carolina Baptist Convention and one of 14 co-authors of the book.

“George Liele was really and truly the first Baptist missionary; there’s no way to get around it. Even before William Carey, or Lott Carey or any of those persons who are so celebrated in Baptist history, there was George Liele,” Driggers told Baptist Press. “And George went out on his own. He was not funded by any missionary society or any group whatever.”

Driggers and others compare Liele to the Apostle Paul of the early Church.

“[Liele] was a missionary if there ever was a missionary. Just like Paul, on his own, he went from place to place. Everywhere he went he preached the Gospel. They’d put him in jail; he’d get out, he’d start a church,” Driggers said. “But everywhere George went or where his disciples went, they’d start churches.”

Southern Baptists formally recognized Liele’s pioneering missions in a resolution at its 2012 annual meeting in New Orleans, on the occasion of the election of Fred Luter as the first African American president of the Southern Baptist Convention. The resolution celebrates Liele as the first overseas missionary from the U.S., noting that historiography has not always reflected the contribution of African American Baptists.

Liele originally had the surname Sharp, after his owner Henry Sharp. Sharp’s friend Matthew Moore, a pastor, had been teaching Liele the Holy Scripture, reading and writing, when area ministers realized they needed to ordain him, and did so in 1775, according to the book.

Sharp freed Liele, who continued to minister in the area until Sharp was killed in the American Revolution and his sons tried to reenslave Liele. At that time, Liele adopted his birth surname of Liele, honoring his father, and in 1783 secured passage to Jamaica as an indentured servant of Col. Moses Kirkland, the commanding officer of British forces in Savannah, Ga. By then, Liele had a wife and four children who sailed with him.

Liele is credited with founding the first black Baptist churches in Georgia and Jamaica, which continue today, and with training missionaries who took the Gospel to West Africa, where Liele’s ancestors were born.

“In Jamaica, he got there and the first thing he did, was gather up a whole group of folks at a racetrack in Kingston, Jamaica and preach to them, and the police showed up and locked him up,” Driggers said. “They’d let him out; he’d go right back to preaching. They’d lock him up [again].”

In Jamaica, the Church of England was the only congregation law allowed, unless the legislature granted special permission.

“We don’t know how many times he was in jail,” Driggers said. “But during that process, in Jamaica, he worked out a respect on the part of the slave owners and the politicians. Over time, they began to respect him.”

Liele’s life was one of precarious balance. He walked a fine line to serve the Lord, appease slave owners, plant a church and win lost souls to Christ. Liele had a reputation of being able to work with people who themselves had conflicting goals, Driggers said.

“He got along well with anybody and everybody, black, white, young, old. He just had a way about him, winning people’s confidence, and they would trust him,” Driggers said. “Liele was a very astute man, there’s no question about it. Theologically, very conservative. He was smart. And he had a reputation of being able to work with folks.”

Liele arrived in Jamaica about 10 years before William Carey preached his famous sermon which created the Baptist Missionary Society in Kettering, England. Liele’s history attracted the attention of theologian and pastor David T. Shannon Sr., now deceased, who pulled together a team of 14 leaders to conduct research and write the book on Liele. Included were pastors, theologians, historians, authors, teachers, attorneys and a Liele descendant.

Liele ushered in a new era for Jamaica, said Noel Leo Erskine, a book co-author, theologian and Jamaican native who grew up in the Ethiopian Baptist Church of Jamaica Liele founded.

“This man was infatuated with preaching and baptizing. I think they should call him the baptizer,” said Erskine, professor of theology and ethics at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology in Atlanta. “He gets on the boat to sail to Jamaica. He jumps off the boat and he baptizes people and he jumps back on. And what a phenomenon that must have been for enslaved Africans, for the first time in their lives, to see a fellow African preaching the Gospel.”

Liele was first accused of preaching a liberation theology during his early imprisonments in Jamaica.

“The word was his sermons were incendiary, they were stirring up the people. He preached on Romans 10:1, ‘Brethren my heart’s desire for Israel is they may be saved,’ Erskine paraphrased. “And he went on to talk about Africans in Jamaica being like Israel in bondage and it was God’s will for them to be freed, to be saved. And he ended up in jail … serious jail, because they say his feet were in the stocks and he was chained … really on death row.”

Anabaptist covenant

Liele turned the tables by implementing an Anabaptist covenant that sought to appease slaveholders and slaves, and allowed Liele to continue a life of ministry. Erskine believes Liele brought with him from Georgia the document entitled “The Covenant of the Anabaptist Church, Begun in America, December 1777, and in Jamaica, December 1783.”

“And so he came up with this covenant to appease the planters and the legislature. And the covenant says clearly there is to be no shedding of blood, no quarrelling among you, no killing among you. Obey your master,” Erskine said. “And he even came up with a bell. The bell would be rung to tell the masters what time they should send servants to church, and he would ring the bell after church and say it’s time to expect your servants to come home.”

Liele’s church was open to all, but slaves could only join with their owner’s permission. While the covenant presented slavery as the norm, Erskine said the document was indicative of a survival tactic slaves and free blacks have employed during oppression. Slaves and other oppressed blacks often used a code language that communicated hopes of freedom, unbeknownst to others.

Erskine references the traditional Negro spirituals “Steal Away to Jesus” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” as examples.

“The master heard that and thought, ‘Oh those people are singing a great, nice song,’ and they’re talking about running away. ‘Looked over Jordan, what did I see?’ That’s talking about going across the Ohio River [and on up] into Canada,” Erskine said. “So the way the language was coded, the master was right there and not understanding. Or a slave person passing looking at the big house, ‘Everybody talking about heaven ain’t going there.’ The codes I think were a crucial part of it.”

Yet, Liele’s approach created tension among African Baptist worshippers in Jamaica, causing his church to split a number of times, Erskine said.

“There was tension there because in his heart, Liele was a contextualist,” Erskine said. “Liele would do what would work. In the end of the day, he wanted his church to survive and he wanted his people to be freed.”

Book co-author and retired Decatur, Ga., Presbyterian pastor Winston Lawson, a Jamaican native, calls the covenant “appeasement with a purpose.”

“So Liele’s apparent conformist and cooperative strategy, assuring planters that he would not use church attendance or instruction as opportunities to plan revolts, derived, no doubt, from his belief that to have half a loaf is better than having no loaf at all,” Lawson wrote in the chapter he authored. “No wonder he was well spoken of by most of the planter class, as historian W.J. Garner attests. In fact, Liele carried his appeasement strategy-with-a-purpose forward by enunciating the aforementioned covenant, not only as a strict religious guideline for members, but as an agreement of loyalty and cooperation with the Jamaican legislature.”

The legislators were planters and slaveholders, Lawson said, and had been accustomed to doing whatever they willed with the slaves they purchased.

For instance, article 16 of the covenant condemned the breakup of families, which was a direct attack on plantation owners, who actively discouraged marriage and opposed the family unit among slaves in every conceivable way, Lawson said. The covenant also established a system of law and governance within the church for its members, which strategically bypassed the civil authorities, who are categorized as “the unjust” in articles 9 and 11.

“It was also a rebuke to the plantation owners, a subtle rebuke,” Lawson told Baptist Press, “because they would just do whatever they wanted to do, whether they were married to the enslaved people or not. It was a kind of underhanded compliment. Even when he was advocating marriage, he was also chastising those who were doing things outside of marriage as the norm for them.”

Liele was himself a slaveholder, evidenced by his last will and testament leaving his eight slaves to his widow Hannah, stipulating they were to be freed upon her death. Liele is believed to have died in 1825 or 1828, according to the book.

Liele never accepted a salary from his church, but earned money through a business transporting ammunition from the naval base in Port Royal to Kingston. He also received monetary contributions from a church pastored by his friend John Rippon in London, England.

Erskine attributes Liele’s ownership of slaves to the influence of George Whitefield, remembered as Liele’s favorite preacher.

‘We’re a little bit ashamed that he caused a little blot there,” Erskine told Baptist Press. “But then … I argue it this way, that they say that his favorite preacher, Liele’s favorite preacher, was George Whitefield, and that he mimicked Whitefield in the way which he preached, with his gesticulations.

“And Whitefield was one of the biggest slave owners in Georgia. [I argue] that it was not unusual, since he came out of Georgia, for preachers to have slaves. So he really didn’t have any good role model [regarding slavery] … in terms of what it meant to be a Christian clergyman.”

“But it seems to me that if you’re involved in that structure of slavery … it comes in like capitalism today. Look at us Christians and how we relate to money,” Erskine said of the temptation toward materialism and greed. “Look at our priorities. It seems to me … that if you come close to absolute evil, it messes you up. Even a lovely man like that, slavery … affected him.”